far more vital than vile

Vultures are one of the only land-based vertebrates able to sustain themselves solely through scavenging for carrion (or, meat from dead animals). While their diet might seem vile, and vultures aren’t necessarily the cuddliest looking creatures, they are vital to maintaining an ecosystem’s balance. They quickly consume carcasses and help limit the spread of disease, as the bacteria-killing acid in their stomachs is highly corrosive and provides a high tolerance to toxins and diseases, such as rabies and anthrax.

Outside of their ecological importance, vultures are intelligent and social creatures who deserve more respect and appreciation. The goal of this series is to highlight their importance and focus on their amazing adaptations and unconventional beauty. It features the three vultures found in the United States: the Turkey Vulture, Cathartes aura, the Black Vulture, Coragyps atratus, and the California Condor, Gymnogyps californianus.

Complete ‘Carrion Committee’ Set in beige

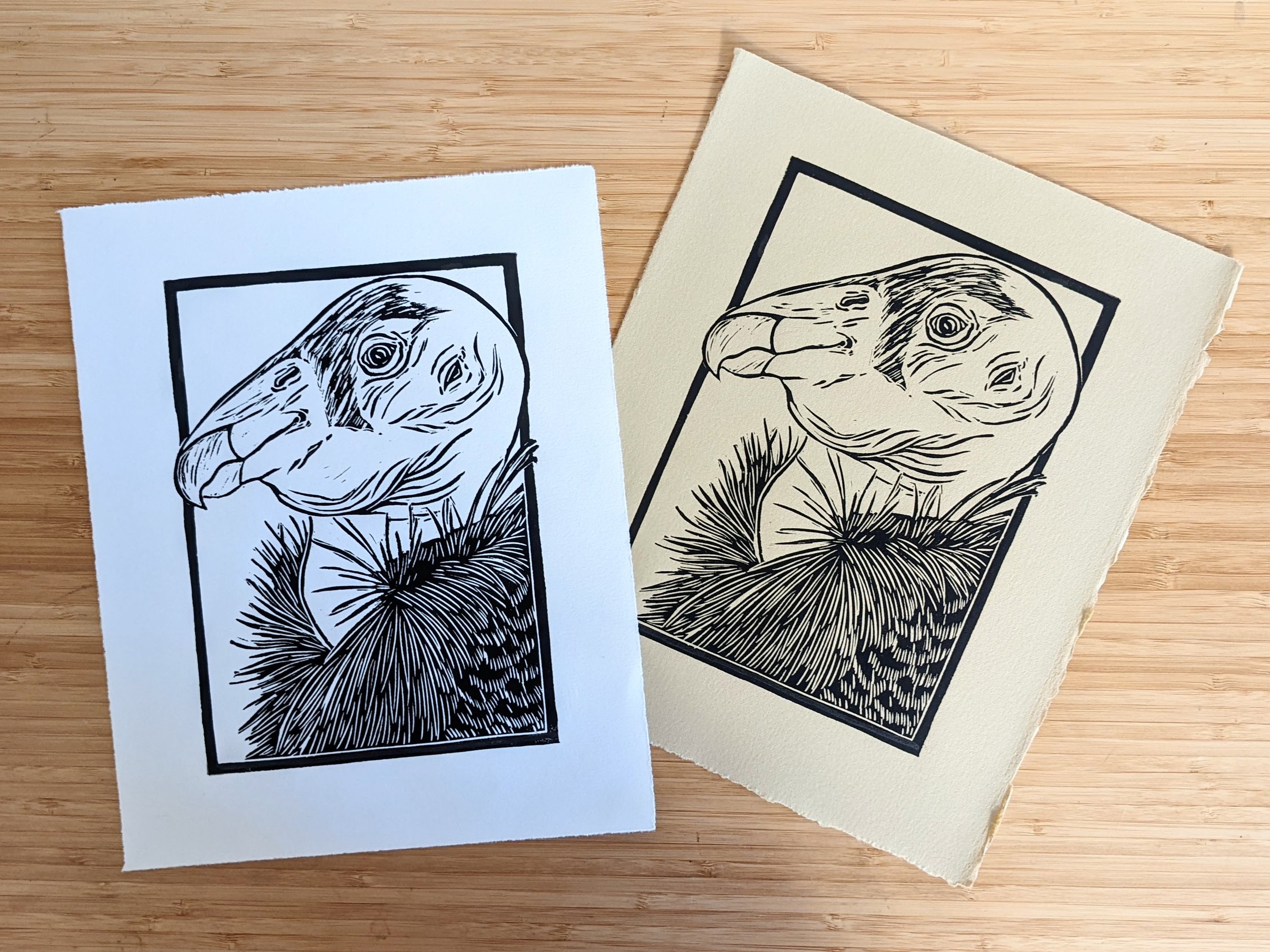

turkey vulture

Cathartes aura

Incredibly common in the Unites States and the most abundant vulture in the country, the Turkey Vulture is a large dark bird, with long broad wings, and an average 6-foot wingspan. When soaring, Turkey Vultures hold their wings slightly raised, make a “V” shape when seen head-on. They have a featherless, bright red head with a pale bill and pale legs- that more so resemble the legs of a chicken rather than a hawk or raptor.

With one of the largest olfactory system of any bird, these vultures years their keen sense of smell to find carrion (even if it is miles away). These birds also have nostrils so large that you can see completely through them and out the other side.

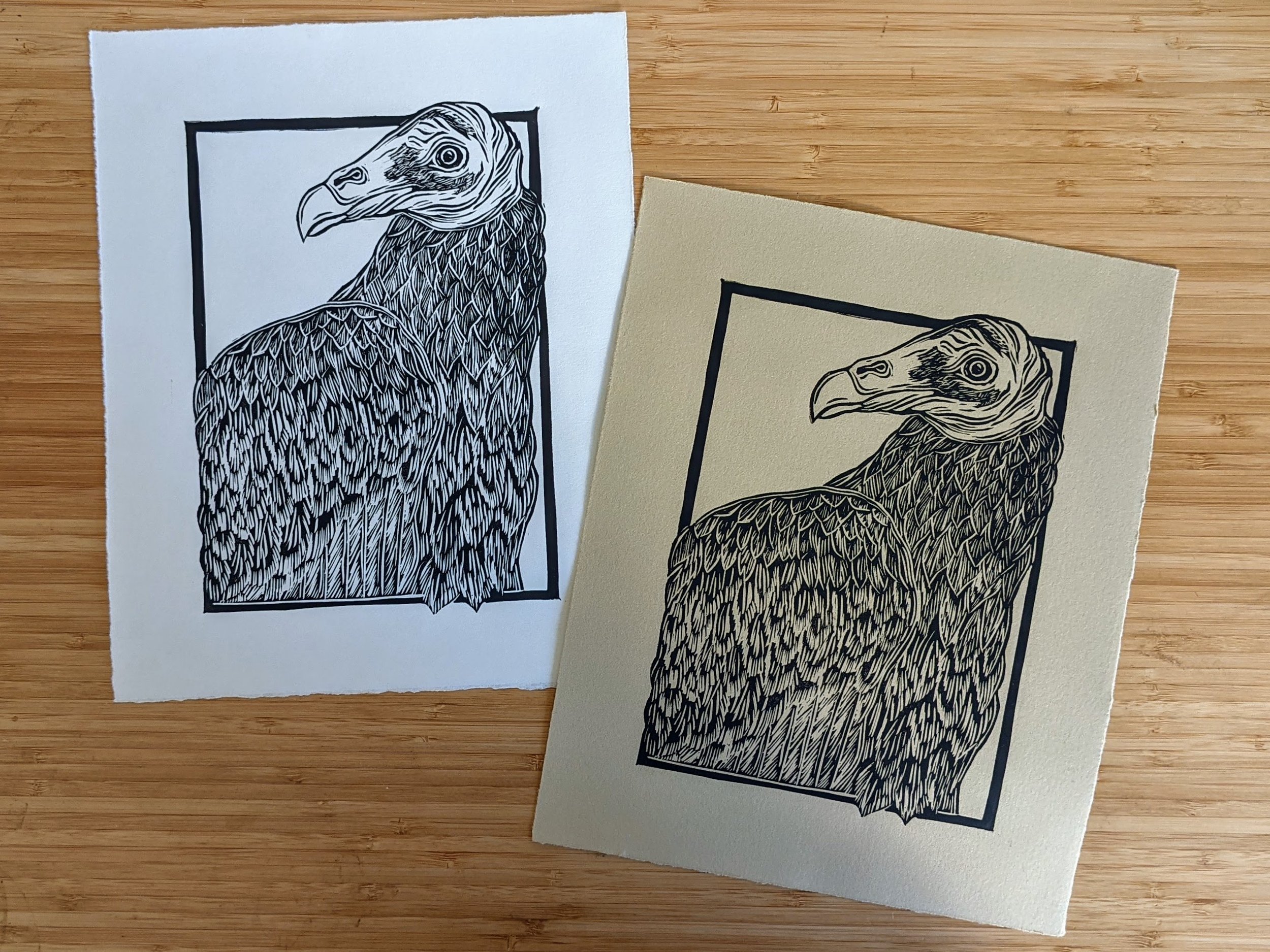

black vulture

Coragyps atratus

While outnumbered in the U.S by their red-headed relatives, Turkey Vultures, Black Vultures have a large range and are one of the most numerous vultures in the Western Hemisphere. Their range extends from the southeastern U.S, through Mexico, and throughout South America. Uniformly black, except for the white patches or “stars” on the underside of their wingtips, they are compact birds that look almost dapper.

While Turkey Vultures rely on their sense of smell to locate carrion (even if it’s miles away), Black Vultures aren’t as well adapted in terms of their olfactory system. Instead, they have learned to take advance of the Turkey Vultures keen sense, and will soar high in the sky, keeping an eye on the lower soaring Turkey Vultures; once they detect a carcass, the Black Vultures follow close behind. While a Black Vulture would lose out to the large Turkey Vulture when battling one-on-on, Black Vultures will flock together and quickly take over a carcass from the often solitary Turkey Vulture.

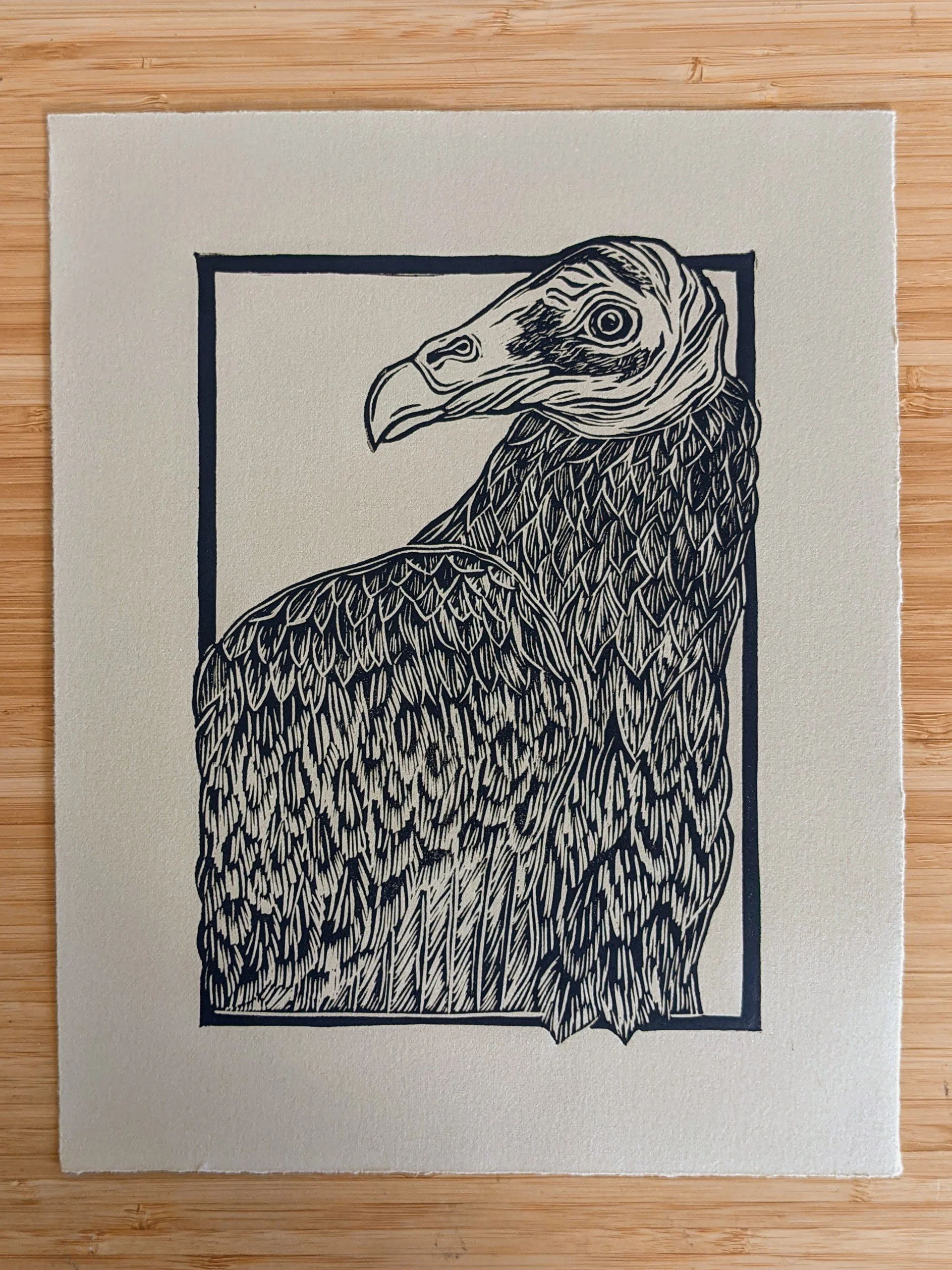

California condor

Gymnogyps californianus

With an over 9-foot wingspan, the California Condor is the largest bird in North America. Their scientific name, Gymnogyps californianus, has its origins in Greek, with gymnos meaning naked (referring to the head), and gyps meaning vulture; californianus is Latin, and refers to the birds’ native range. Their population fell to 22 individuals in the 1980s, but there are now roughly 230 free-flying birds in California, Arizona, and Baja California, with another 160 birds in captivity.

Their recovery has been long process due to their extremely slow reproductive rate. Female condors only lay one egg per nesting attempt (which isn’t always annually), and the young depend on their parents for over a year, and can take 6-8 years to reach maturity.

When claiming a carcass, California Condors often dominate other scavengers (with the Golden Eagle and its’ sharp talons being the exception). They also can survive 1-2 weeks without eating. Once they are able to locate food, they can eat their fill, storing up to 3 pounds of meat in a section of their esophagus (called the crop) before leaving. Lead poisoning (primarily from spent ammunition found in carcasses) remains a severe threat to their long-term survival prospects.