west coast wonders

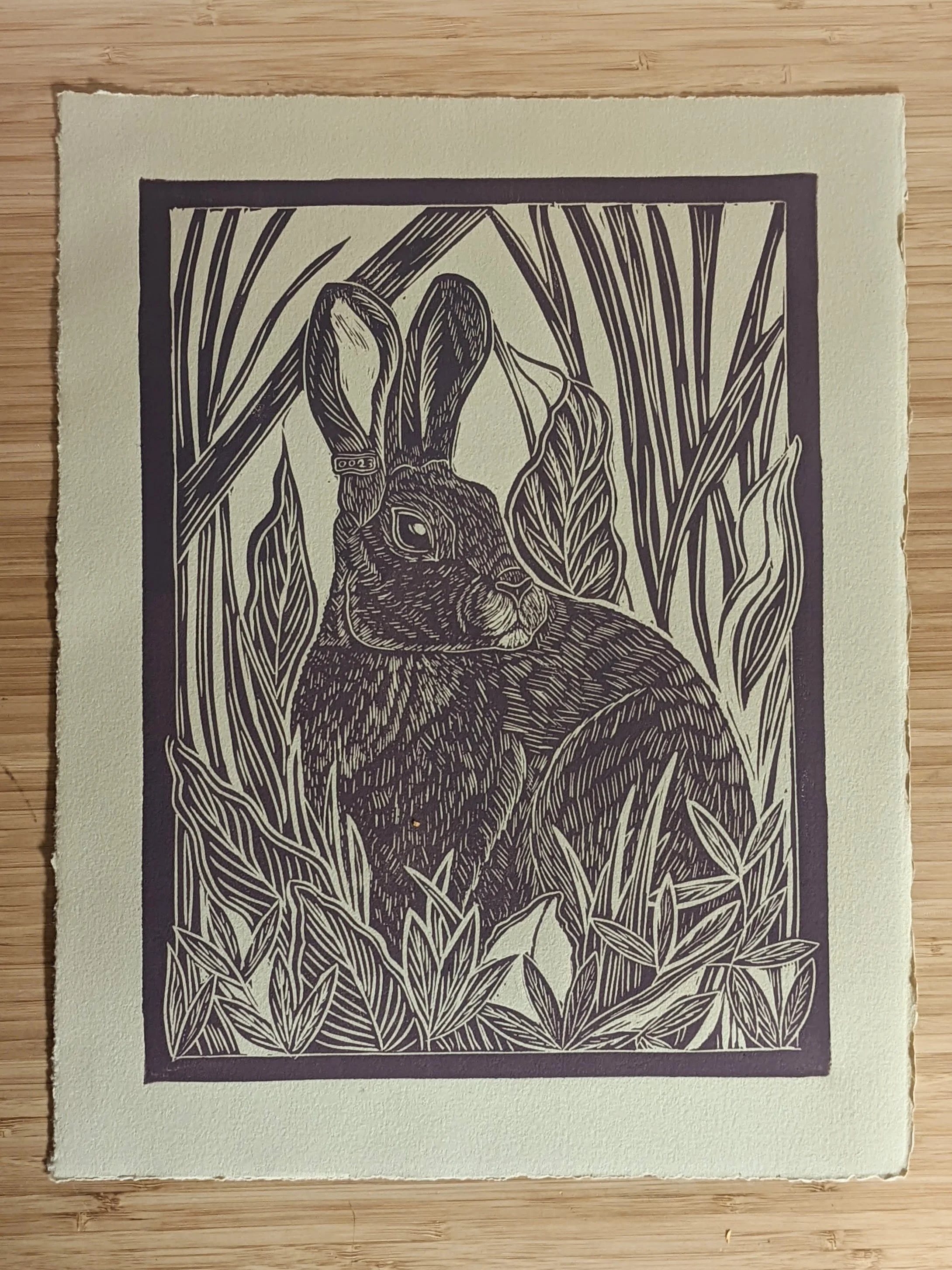

Riparian Brush Rabbit

Sylvilagus bachmani riparius

This small brown and white rabbit, weighing in at only 1.5 pounds, is a subspecies of brush rabbit and among the rarest mammals in California.

The riparian brush rabbit was once believed to be reduced to a single population in Caswell Memorial State Park, but another population was discovered near Lathrop, California, in 1998. Since this discovery, a third population has been reintroduced to the San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge. It was listed as endangered on February 23, 2000.

The biggest current threat to the species is a fatal virus that infects rabbits across the western United States. Other threats to the species include seasonal flooding of habitat, development and land use change, wildfire, drought and predation.

But, recovery efforts are underway! Organizations such as River Partners, USFWS, CDFW, and the Conservation Society of California (Oakland Zoo) have been working together to vaccinate these rabbits against disease, protect and repair habitat, and educate the public on their story.

The 11” by 14” print below features the riparian brush rabbit, nestled in the brush, and sporting its own research tag. While these tags would normally represent each individual rabbit that’s been vaccinated, the tag in these prints read “OO23”, commemorating the first Overlooked Opossum print in 2023.

ringtails

Bassariscus astutus

With a cat-like body, a fox-like face, large oval ears, and a bushy black and white tail, the ringtail is a wonderful sight- that is, if you ever manage to see one! Also called ringtail cats, or miner’s cats, these creatures aren’t related to cats at all. Their closest relatives include the coati and the raccoon.

These elusive creatures are active primarily at night, and occasionally at dusk. They are excellent climbers, with several behavioral and physical adaptations that allow them to navigate the rocky outcroppings in deserts and chaparral. Ringtail cats are capable of ascending vertical walls, trees, rocky cliffs, and even cacti. They can rotate their hind feet 180 degrees, allowing them a good grip during their descent.

The 7” by 14” print below features the ringtail doing what it does best: climbing.

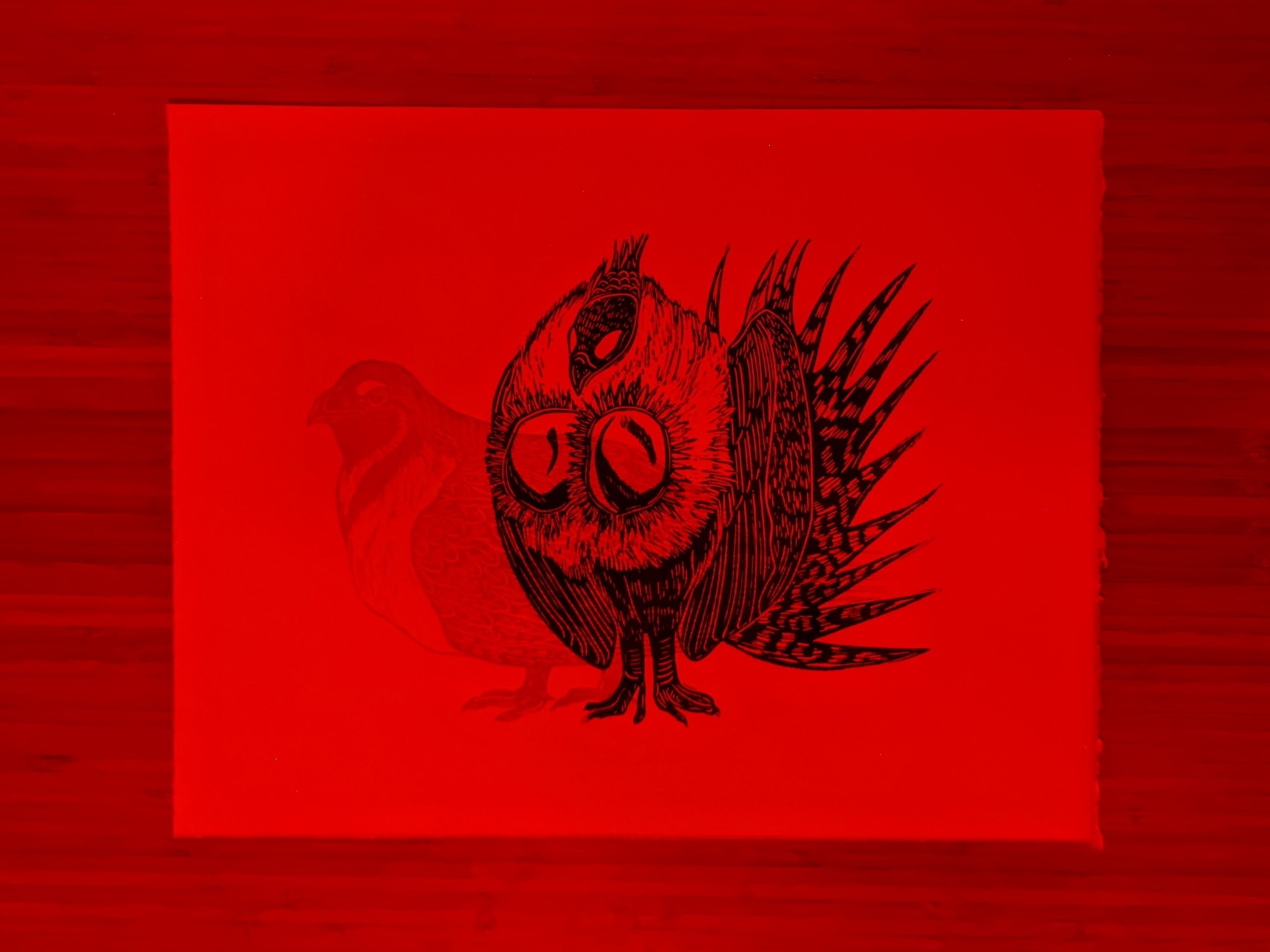

greater sage- grouse

Centrocercus urophasianus

For the majority of the year, these large and chubby birds blend into the dense cover of the sagebrush steppe in western North America. However, come late winter and early spring, these birds take center stage with one of the best examples of the complex breeding system known as lekking: where males gather together in designated areas to perform courtship displays for females.

These displays are extraordinary. The males will repeatedly gulp air while stepping forward, holding up to a gallon of air in a pouch of their esophagus, then forcefully release it. They inflate the yellow, balloon-like pouches on their chest- and, as they rapidly inflate & deflate, create a series of loud echoing pops. These displays are loudest off to the sides, rather than straight ahead, so the males will stand to the sides of the females they are attempting to impress. (However, don’t let these masculine displays fool you- the females are 100% in charge of this process and who they choose to mate with).

Traditional lekking grounds can be used for years- with males being incredibly territorial. Due to their population ties to specific habitats and lekking grounds, the Greater Sage-Grouse is particularly vulnerable to even small amounts of habitat fragmentation and disturbance.

The 11” by 14” print below features both views of the Greater Sage-Grouse- the male in a relaxed position, and inflated for a full display. With one position printed in red, and the other in blue, the viewer can see each depending on whether they look through a blue lens or a red lens.

Greater Sage-Grouse Print; 11" by 14"

Greater Sage-Grouse Overlapping design

Greater Sage-Grouse print under blue film

Greater Sage-Grouse print under red film

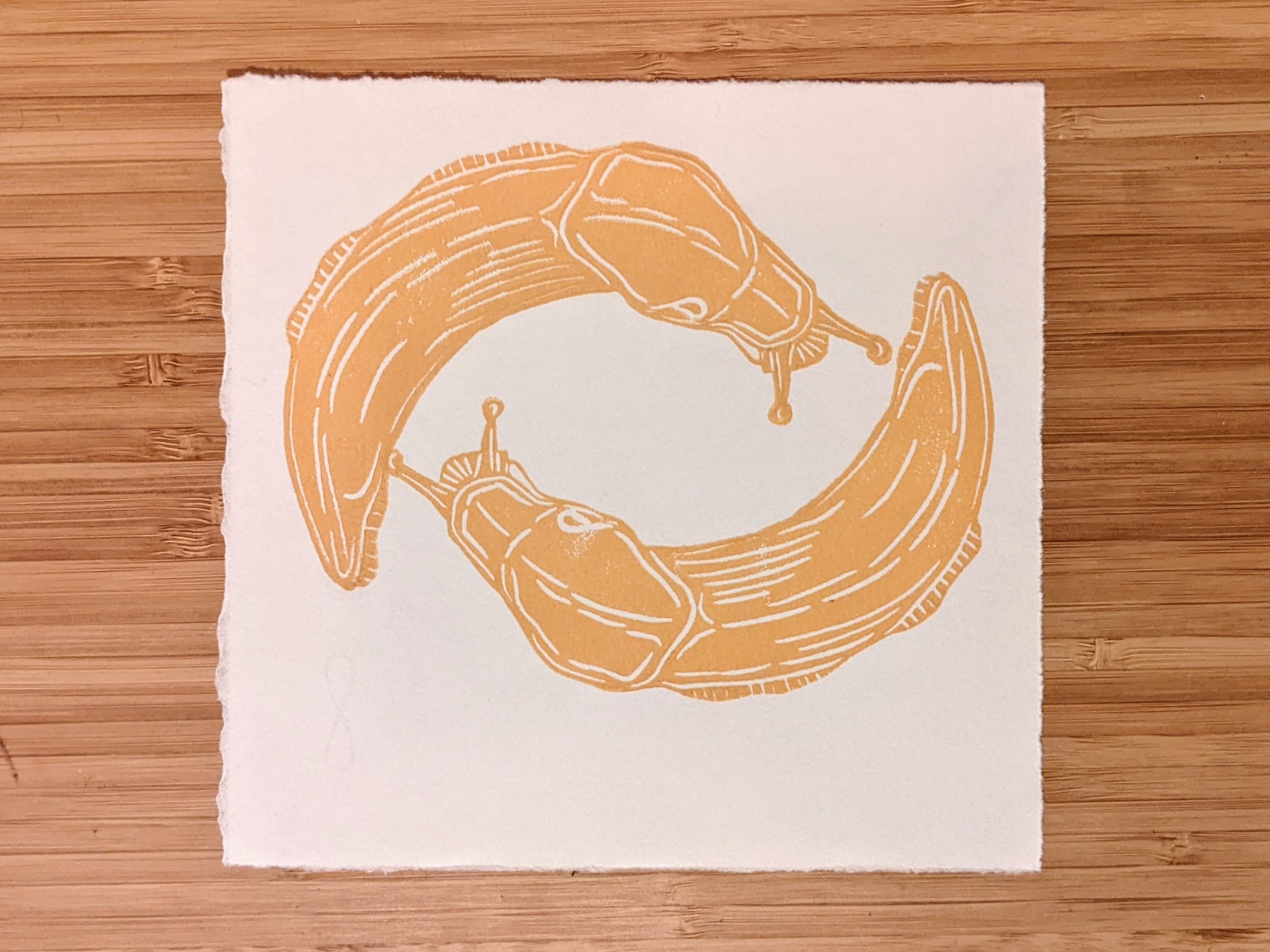

banana slugs

genus Ariolimax.

Often found on the dense, moist forest floors of the Pacific Northwest, these slugs range from Central California all the way to Alaska. These bright yellow creatures earned their names due to their uncanny resemblance to the fruit (though sometimes, they can appear “overripe”, with some additional brown spotting).

To avoid dehydration, banana slugs produce a thick mucus to stay alive. This slime helps protect them from drying out, and also can help deter predators- it is also an anesthetic, meaning it will make a predator's tongue or throat go numb.

This slime also contains pheromones to attract other slugs for mating. Banana slugs are hermaphrodites, meaning they possess both male and female reproductive organs, and reproduce by both exchanging sperm with their mate. But there is an odd twist: they will sometimes take part in apophallation (the biting off of the penis). It’s unknown exactly why this occurs- some say it is an act of self-preservation, in case one slug becomes stuck during the mating process, and others argue that is a calculated move at sperm competition.

This 6” by 6” banana slug print features two banana slugs entering into the beginning stages of their complicated (and potentially painful) courtship: encircling each other to make sure they a good match for what might follow.

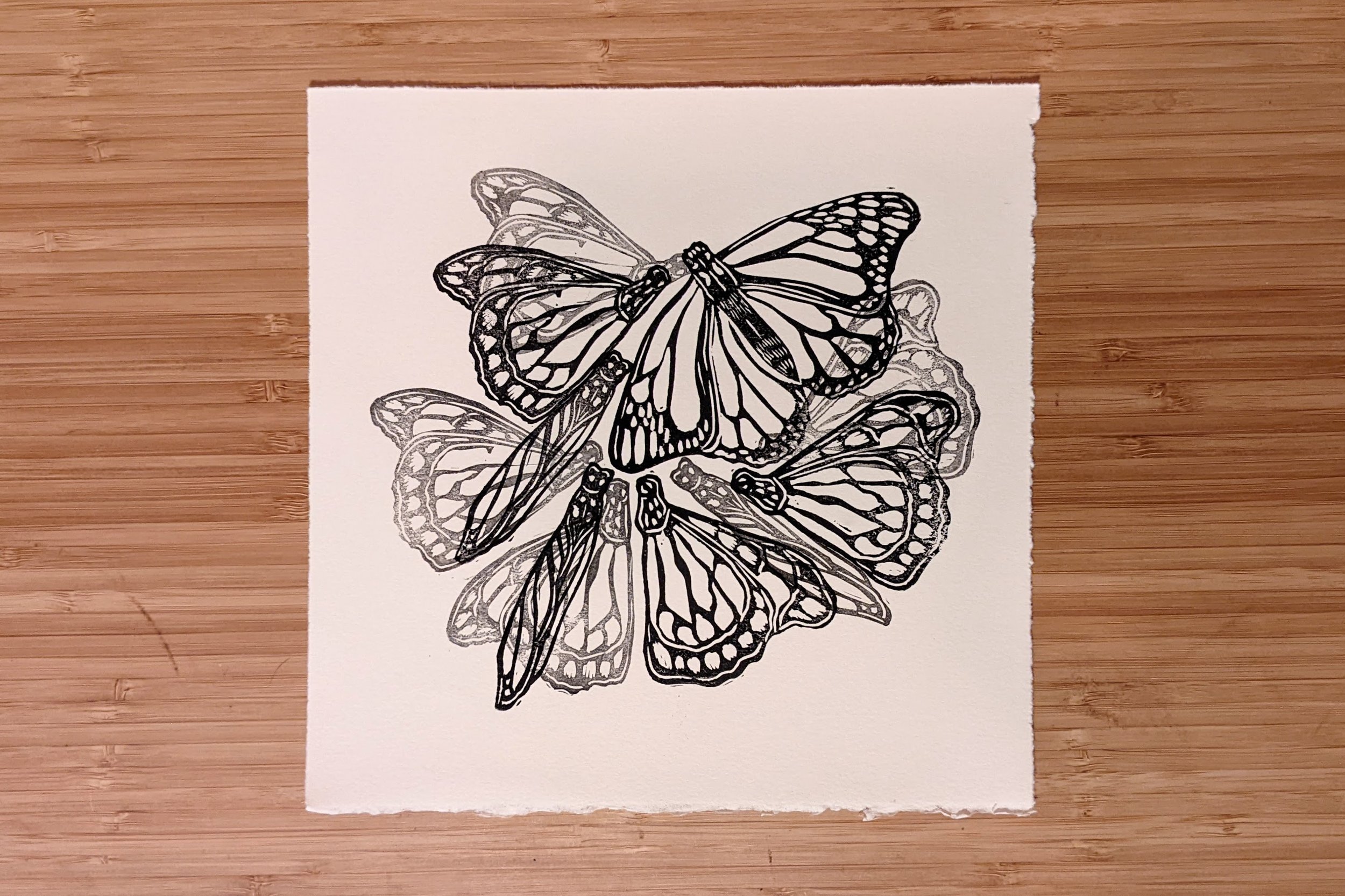

monarch migration

Danaus plexippus

As one of the most recognizable and well-studied butterflies on the planet, the Monarch needs no introduction. Famous for their seasonal migration, millions of monarchs migrate from the United States and Canada south to California and Mexico for the winter.

Monarchs living west of the Rocky Mountain range in North America overwinter in California along the Pacific coast near Santa Cruz and San Diego. These microclimatic conditions are very similar to that in central Mexico. Monarchs roost in eucalyptus, Monterey pines, and Monterey cypresses in California.

Monarchs cluster together to stay warm- sometimes with tens of thousands of monarchs clustering on a single tree. This 8” by 8” print features a small cluster of Monarchs, huddled together as they wait out the winter weather.